AT A GLANCE

This framework provides a set of recommendations for postsecondary institutions and employers to support Black learners and workers to build professional social capital. It expands on a related JFF market scan that maps the landscape of nonprofit and social enterprise-led social capital initiatives.

Professional Social Capital: A Key to Black Economic Advancement

In today’s dynamic and rapidly changing economy, there is no guaranteed path to economic advancement. This is particularly true for Black learners and workers, who experience higher unemployment rates and lower wages and have significantly less wealth than their white counterparts with the same level of educational attainment.

While many education and workplace strategies for Black learners and workers simply focus on credential attainment, this is not enough. In fact, these disparities are the result of profound intersecting challenges—from occupational segregation, which can begin with the choice of a college major or type of credential, to workplace bias and discrimination. But there is another factor, rarely discussed, that demands our immediate attention: Black learners and workers have less systemic access to build and maintain professional social capital.

Professional social capital—the crucial connections, networks, and resources that help people understand, access, and navigate educational systems and the labor market—is a proven accelerant to learner and worker success in today’s society. While we strive to create a more egalitarian economy in which social capital, personal networks, and common affiliations do not determine a learner or worker’s opportunity, that is not yet a reality. Today, social capital remains a critical resource that helps people understand, find, and secure opportunities, and identify workplace sponsors who can advocate for their promotion and ongoing advancement.

While all communities have their own wealth of relationships and connections, studies show that Black people living in the United States, particularly Black men, have smaller networks than other racial groups, and that Black workers, particularly Black women, are less likely to find sponsors and mentors in the workplace.

We believe addressing these kinds of disparities in professional social capital is necessary for driving equitable economic advancement for all. With this goal in mind, Jobs for the Future (JFF), with support from the University of Phoenix and guidance from a nationally recognized advisory council, set out to develop an action-oriented framework for postsecondary education and training providers and employers— to ensure Black learners and workers can gain and utilize professional social capital to begin, expand, and advance their careers.

About JFF's Center for Racial Economic Equity

As part of our mission to drive economic advancement for all, JFF’s Center for Racial Economic Equity is partnering with stakeholders across the learn and work ecosystem to focus on two foundational priorities: disrupting persistent occupational segregation and developing innovative solutions to eradicate the longstanding Black-white wealth gap.

As outlined in our action plan to advance Black learners and workers, Achieving Black Economic Equity: A Purpose-Built Call to Action, professional social capital is relevant to both those priority areas: it is a key resource to help ensure Black learners are aware of and can access and advance in high-growth and high-wage sectors of the economy, and pursue entrepreneurship and wealth creation and preservation.

Future Center work will continue to build upon our call to action by identifying, disseminating information, and supporting implementation of innovative programs, policies, and strategies that successfully address systemic barriers to equity for Black Americans and promote opportunities for economic advancement and wealth-building. This will include opportunities to pursue implementation of our recommended professional social capital strategies with key stakeholders in the learn and work ecosystem. For more information about JFF’s Center for Racial Economic Equity, visit here.

About this Framework

This framework expands on a JFF market scan that maps the landscape of nonprofit and social enterprise-led initiatives specifically designed to help Black learners and workers accrue professional social capital. JFF is leading both projects in partnership with the University of Phoenix, building upon findings from the university’s Career Optimism Index.

The strategies in this framework are designed for two key groups: postsecondary institutions and employers.

We recognize the importance of partnership across these two actors and the broader ecosystem to promote social capital creation for Black learners and workers and hope to expand upon this further in future work.

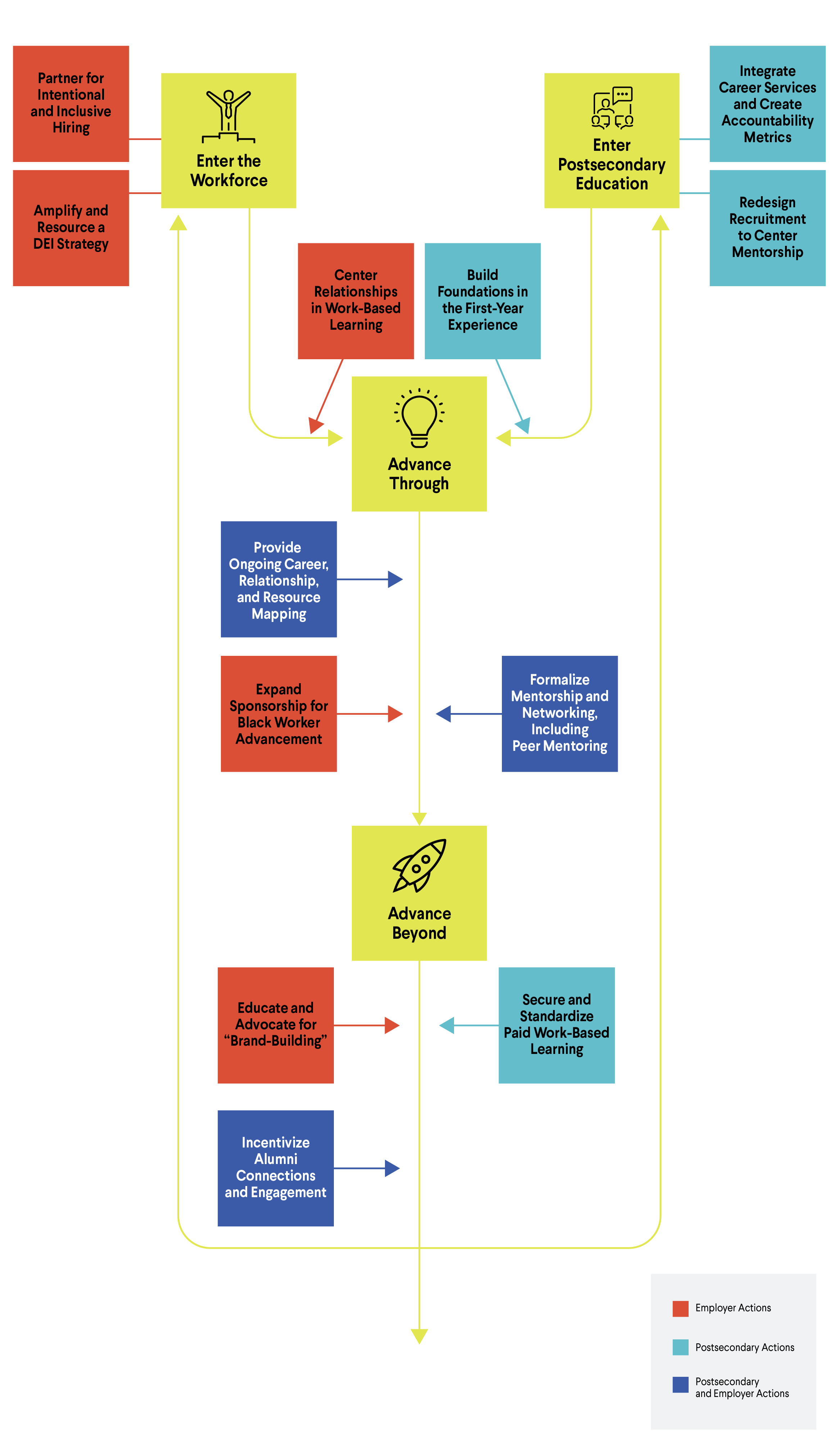

To demonstrate the interconnectedness of the postsecondary education and workforce exploration journeys when it comes to social capital creation, please see this graphic:

Click image to zoom

The actions we recommend build upon findings from our market scan, including the identification of five elements that we believe the most innovative social capital strategies include:

Elevate Current Assets

Focus on participants’ strengths and existing networks, rather than calling attention to what they might lack

Build Relationships

Emphasize the importance of connecting learners and workers to people with whom they can have sustained, supportive relationships

Make Connections and Introductions

Help learners and workers meet people who can assist them with specific immediate needs

Formalize Career Onboarding

Connect learners and workers to the next steps in their career journeys, matching individual needs in terms of pay, scheduling, and supports

Enable a Continuous Learning Journey

Enable people to continue building and activating professional social capital throughout their lives, and benefit from their networks, relationships, information, and resources at every stage of their career and learning journeys

Postsecondary Education and Training Providers

Common wisdom calls for learners to use postsecondary education and training to attain valuable labor market skills and credentials. Community colleges, four-year universities, and short-term training providers can also take key actions to help their students to attain, understand, and utilize professional social capital. While the key actions in this section have the potential to benefit all students, they are particularly critical for Black learners and other groups who are underrepresented in these settings and at the top of our economy.

The section identifies actions institutions can take as learners begin, continue, and advance beyond postsecondary education and training.

Beginning: How Institutions Can Set Up Black Learners for Success

These key strategies ensure Black learners and workers can build social capital as they enter postsecondary education and training programs.

Redesign Recruitment to Center Mentorship

Redesign Recruitment to Center Mentorship

Recruitment should not simply be viewed as an opportunity to increase Black learner enrollment, but a chance to build relationships that introduce a range of postsecondary education and training pathways and build professional networks. Recruitment programs should emphasize early outreach, in partnership with K-12 schools and local community-based organizations (CBOs), and incentivize current students, faculty, and staff to invest in Black learners’ postsecondary journey through mentorship. These relationships will provide Black learners with a point person in their social capital network who can share information about a variety of pathways, support learners in their decision-making process, connect them to additional sources of support, and stay in touch during and beyond enrollment.

Colleges that integrate service-learning experiences, including mentoring, into credit-bearing courses can engender growth for both students and the communities they serve. These relationships support mentees in their exploration of postsecondary goals and interests and completion of enrollment and financial aid applications, as well as provide a trusted and invested guide.

The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s Collegiate G-Force is a work-study mentorship program that uses financial aid funds to employ college students as mentors in community centers and high schools. Goals include improving high school completion rates for Black and Latinx learners, introducing them to postsecondary pathways, and augmenting their social capital networks with a point person specifically designated to assist with their learner journeys. Ohio State University launched a similar mentorship program that, although unpaid, connects college mentors to mentees in both a local high school and a middle school, engaging Black learners at an even earlier age.

Build Foundations in the First-Year Experience

Build Foundations in the First-Year Experience

During orientation and throughout the first-year experience, postsecondary institutions should create a foundation for Black learners to build social capital. This must include helping learners understand the importance of social capital, mapping learners’ education and career trajectories, and discussing how to leverage and activate their current assets, including institutional resources, program- specific opportunities, and acquaintances to achieve their goals. Using an asset- based model recognizes the strengths and experiences learners have, rather than focusing on what a learner might lack. Career services staff are often positioned to guide learners through this mapping process, and trained faculty advisors and instructional staff mentors are ideal partners to provide supplemental support. These sessions should be mandatory for all students in order for this strategy to be most effective.

26% of all learners and 34% of Black learners do not continue in postsecondary education beyond their first year. However, first-year students who feel a connection with their university are more likely to continue, particularly students from underrepresented backgrounds.

Connected Scholars is a proprietary program that offers a secondary- and postsecondary-level courses to help students understand the value of social capital. Students learn how to build and maintain a network, as well as identify and develop relationships with potential mentors. At Big Brothers Big Sisters of Eastern Missouri (BBSEMO), the secondary-level course was adapted to help students expand their existing networks and strengthen relationship ties. When implemented at the postsecondary level, the course allows institutions to integrate career services into a first-year experience, where all learners can learn to build and leverage their social capital.

Integrate Career Services and Create Accountability Metrics

Integrate Career Services and Create Accountability Metrics

Before Black learners enter postsecondary institutions, consider how career services can be positioned to best facilitate the growth of Black learners’ professional social capital. Key strategies may include elevating career services to the executive team, integrating career services across the institution and learner journey (with learner design input), and measuring social capital-related metrics in institutional key performance indicators (KPIs).

Career services is often an isolated resource, which creates obstacles to access. For example, 76% of schools separate academic advising and career counseling, making it difficult for first- generation learners to access and navigate the resource. When elevated, career services leaders and staff gain increased visibility and institutional influence. With better access to internal and external partnerships, such as academic department leaders and regional employers, career services can develop high-quality interdepartmental programming that enables learners to build strong networks throughout their education and training journey. When social capital-related metrics are included in institutional and career services KPIs—and critically, when this data is specifically disaggregated by race—institutions can understand what is and isn’t working and adapt accordingly.

John Hopkins University developed an institution-wide strategic plan to revamp its career services. With a new name, Integrative Learning and Life Design, career services now sits in the provost’s office where it is thoroughly integrated with other departments, including academic affairs. Its KPIs, such as post-graduation employment rates, now factor into how the institution understands its own success. The success of this initiative has spread to several other institutions, including Vanderbilt University and Emory University.

Continuing: Helping Black Learners Strengthen Ties and Gain Resources

As Black learners and workers advance through postsecondary education and training, institutions can help them increase their social capital along with their skill sets to utilize it.

Formalize the Mentorship Experience

Formalize the Mentorship Experience

A formalized, institution-wide, mandated mentoring program can help Black learners expand their networks, build meaningful relationships with professionals in their field, and receive guidance about their pathways. Mentorship programs should match faculty and instructional staff to learners based on mutual interest and include 1:1 meeting guidelines as well as opportunities to network with other mentors. It is critical that mentor assignments are made equitably, and that all faculty and instructional staff—not just Black faculty and staff—are trained to provide culturally relevant and supportive mentorship for Black learners. Faculty and staff, especially in predominantly white institutions (PWIs) must understand the impact of microaggressions on Black learners’ well- being and learning outcomes and create safe and inclusive spaces for Black learners to thrive.

A recent survey found that a mentor who encouraged learners’ goals and dreams was the single most important determinant of success in work and life for college graduates. However, mentorship is often not formalized or distributed equitably among students and faculty. Black learners report feeling more safe and familiar with Black instructors, leading many Black faculty to allocate their non- classroom time to mentoring, and reducing capacity to further their own research and scholarship, which can impact their success in the promotion and tenure process. PWIs must account for this by sharing mentorship responsibilities across all faculty and staff with the appropriate training and support, and including student mentorship in the tenure review process. One study found that faculty who received DEI training made positive attitudinal and curricular changes, which translated into learners’ increased sense of community, personal growth, and conflict resolution skills.

Muhlenberg College, a PWI, wanted to develop an effective and meaningful mentoring program that met the needs of students from underrepresented and marginalized groups without overtaxing faculty and staff of color. The new program, Emerging Leaders, pairs each learner with three mentors: a faculty advisor, a staff mentor, and a peer mentor. Program leadership created culturally-aware training for mentors to address issues of race and identity, and made sure that all faculty advisors demonstrated a commitment to inclusive pedagogy, equity, and justice. Related training resources are available at Students at the Center and American University’s Center for Teaching, Research & Learning.

Require Ongoing Career Advisory Engagement

Require Ongoing Career Advisory Engagement

Check-ins and other engagements with career services should be mandatory and tailored to each learner throughout their journey. Regular check-ins can build upon the work done in orientation and the first year, and introduce work- based learning and other opportunities that allow Black learners to expand their professional networks. This should include working with learners to help them reflect on and assess their newly acquired skills, networks, and experiences; discussing strategies for forging new professional relationships; and identifying opportunities to contribute to others’ professional social capital, including the institution’s alumni network. Wherever possible, academic services should reinforce career services messaging, so learners see this as a seamless, interconnected, and equally important set of offerings. Postsecondary institutions should also consider using client relationship management software to standardize and document these meetings, including helping track disaggregated performance data and preparing for potential changes in staffing.

Learners who use career services on an ongoing basis are shown to receive career advice from a wider variety of professional networking sources; they are also having conversations with networking contacts more frequently, as compared to learners who don’t use career services. Studies show that Black learners are most likely to find advice from their career services office helpful — with 48% of Black learners saying so, compared to 28% of their white peers. However, opt- in structures are not working well, with as many as 78% of students reporting rarely or never visiting their career center. Mandated, periodic, and integrated career services can ensure more Black learners benefit.

The University of Baltimore took elements from the GROW coaching model to create a Career Cycle with four phases completed over the course of a learner’s education and training. Each phase includes a learning outcome and actionable step to help learners strategize a path toward their goals. The University of Baltimore considered instituting a new, required course for the Career Cycle, but ultimately decided to integrate it into key academic courses instead for a seamless experience. This model aligns with JFF’s Guided Career Pathways framework, and could be even more effective with an additional check-in that strategizes explicitly with learners on how to expand their professional network and activate their social capital.

Maximize Peer Mentoring and Near- Mentoring

Maximize Peer Mentoring and Near- Mentoring

Institutions can support peer communities— such as student organizations, affinity groups, and Greek life— by providing resources, training, and guidance to student leaders to make the importance of networking and resource- sharing more explicit. This can facilitate introductions among all learners to help them form more loose relationships and acquaintances, and host safe and inclusive events that encourage learners to create bonding and bridging relationships. Institutions should also create online student-only engagement opportunities such as directories, forums, or listservs, where learners can freely ask questions and share information.

Studies have found that near- and peer-mentoring can improve learners’ ability to actively mobilize social capital in pursuit of their education and career goals, develop confidence to reach out and work with professors, and navigate the social and physical environment of college. Studies have also shown the value of offering both bonding and bridging relationship-building opportunities for students. One study found that 18% of Black learners considered their friends to provide meaningful mentorship, compared to 4% of white students. At the same time, research shows that communities with more friendships across class lines are correlated with a higher likelihood of upward mobility. Providing support for social engagement both within and across groups is a critical role for institutions to play.

The City University of New York (CUNY) developed the Black Male Initiative that prominently features culturally competent peer-to- peer mentoring, encouraging bonding and relationship building between Black men. The initiative also opened up its eligibility to non-Black learners, creating opportunities for bridging social capital. CUNY’s goal is to have the Black Male Initiative institutionalized and absorbed into academic departments and student affairs offices at all of their campuses, signifying their commitment to promote equitable opportunities for Black men, and to integrate these opportunities throughout the postsecondary journey.

Advancing : Creating Lifelong Learning Networks and Partnerships

Intentional institutional support remains critical as Black learners explore career opportunities and transition to the workforce.

Secure and Standardize Paid Work-Based Learning

Secure and Standardize Paid Work-Based Learning

Career services must go beyond on- campus career fairs and networking events, and advocate for their Black learners and graduates by soliciting employer partnerships that can lead to work-based learning (WBL) and internship opportunities for learners and graduates. When enough opportunities are secured, college leaders and staff should integrate for-credit, paid work-based learning opportunities as a core requirement for every program. Making WBL mandatory and universal will ensure Black learners gain career exposure and professional social capital creation throughout their postsecondary experience. As noted earlier, institutions must direct sufficient resources and staff to career services to make this work possible.

Without a doubt, WBL and internship opportunities are among the most effective strategies for increasing learners’ professional social capital and success in the labor market. Internships, in particular, are a key entry point for many full-time high-wage careers, and yet many internships are procured via word-of-mouth and relationships. Black learners have less access to these opportunities compared to their white peers, creating a disparity along racial lines. Postsecondary institutions can challenge this disparity by providing Black learners with increased access to WBL and internships, and by serving as advocates, encouraging employers to extend equitable opportunities to Black learners to build relationships and skills for ongoing connections to the workplace.

Students in Northeastern University’s cooperative education program (co-op) alternate 4-6 months of academic study with 4-6 months of full-time work experience. 96% of students participate in at least one co-op, providing valuable career experience and professional social capital prior to graduation; 93% of students are employed or in graduate school full-time upon graduation. All students meet with their designated co-op advisor regularly, and take a course preparing them for workforce entry. College leaders and staff build strong relationships with employers, encouraging them to create opportunities for Northeastern students and to hire their students once they graduate. While Northeastern is a PWI, this model can be applied to institutions with higher Black enrollment as well.

Incentivize Alumni Connections

Incentivize Alumni Connections

Postsecondary career services leaders should incentivize and recruit graduates to “pay it forward” by mentoring Black learners at their institutions. The benefit goes both ways: alumni can identify potential talent for their companies or add community service to their professional resumé, and students can expand their networks for social-capital building. Institutions can also create opt-in directories where alumni can indicate their industry, current employment details, and contact information, allowing current learners to search for and connect with potential mentors.

Early career Black professionals are shown to have a very strong commitment to “pay it forward” and share their social capital with others. Unfortunately, data suggests that postsecondary institutions are not fully utilizing the potential of their alumni networks, often missing opportunities to activate an alumni network in service of current and prospective learners. A redesigned alumni strategy can provide recent graduates with an asset-based framing of their own network, recognizing themselves as agents of social capital with institutional power and resources to help other learners form vertical connections.

In New York University’s Media, Culture, and Communication department’s Alumni Mentor Program, students are matched to an alumni mentor based on their shared interests. Mentors and mentees meet 1-2 times a month, and mentors are encouraged to allow mentees to attend work events and shadow at their offices. Brooklyn College’s similar Alumni Mentor Program includes a mentee training module that learners must complete before meeting their mentor, helping ensure that learners understand how to utilize their mentoring relationship to its fullest. Stony Brook University’s inaugural Alum-in-Residence program had an alum spend one full day on campus to share insights on professional success, answer career or industry-related questions, and provide individual mentoring sessions. While temporary, this model could be a successful lower-touch approach.

Metrics & Evaluation

All these strategies demand that institutions evaluate success by identifying and monitoring key performance indicators.

These may include:

- Metrics on Black learners’ faculty and staff mentorship

- Work-based learning, internship, and job placement rates

- Self-reflections of the quantity and quality of relationships learners made during their postsecondary journey

This list is not meant to be exhaustive because, as noted earlier in the framework, the effects of social capital creation, particularly among Black workers, remains understudied, and there is room to strengthen evaluation of program interventions. For more resources and guidance, please see the Christensen Institute’s framework for measuring students’ relationships and networks, and the Search Institute’s literature review on defining and measuring social capital for young people.

Employers and Workplaces

The drive to embed social capital gains into postsecondary education and training is only successful if the efforts translate to meaningful labor market outcomes, including high-quality job placement and advancement opportunities for Black workers.

This section of our framework identifies key actions employers can lead in to support learners and workers to understand, attain and consistently activate professional social capital, building upon JFF’s Impact Employer Framework. Our strategies center mentorship, community, and partnership because that is where we see the most opportunity and emerging innovation.

This is critically important work, and an area in which employers and workers face a disconnect: the University of Phoenix Career Optimism Index found that only 61% of Americans said they have someone in their professional life who advocates for them, while 91% of employers believe that their workers have this.

While the key actions in this section have the potential to benefit all workers, they are particularly critical for Black workers and other groups who disproportionately experience higher unemployment rates and lower wages and rates of advancement. The section is organized into three categories: actions employers can take as workers begin, build, and expand their careers.

Beginning: How Employers Can Support, Retain, and Advance Workers

These actions can help organizations create social capital gains for Black workers, prioritizing company diversity and inclusion and correcting workplace inequities.

Amplify and Resource a DEIB Strategy

Amplify and Resource a DEIB Strategy

Many large employers name DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) as a value, but fewer provide adequate stature, staff, budget, and training to shape their workplace to embrace and promote all working styles and backgrounds. Elevating an organization’s DEIB lead (often referred to as a Chief Diversity Officer or CDO) to the executive team can help signal the importance of this work in the company culture, and makes a CDO a partner to decision-makers on policies and budgets. This may also include investing in Employee Resource Groups (ERGs), Business Resource Groups (BRGs), and other environments that help build community and support for Black workers.

Embracing and prioritizing equity and inclusive culture is key to attracting and retaining talent, especially among GenZ workers. It is not enough to hire a diverse workforce if employers are unprepared to make them feel safe, included, and supported—critical requirements for staff success and retention. Many employers are hiring or creating Chief Diversity Officers to lead this work—but many are leaving for lack of support. Robust investment in DEIB infrastructure and leadership is required to enact this culture shift.

In 2019, Genentech’s CEO hired the company’s first CDO as a direct report, signaling the value of a DEI lens in business decisions. The company also invests in 13 ERGs, known as DNA Groups (Diversity Network Associations), that help workers build a professional network, foster community, and drive professional development.

Center Relationships in Work-Based Learning

Center Relationships in Work-Based Learning

For many Black learners, work-based learning, such as internships or apprenticeships, is a first professional experience in their chosen field. While employers should follow WBL best practices, linking instruction to critical job responsibilities and specific lines of work, WBL should also be relationship-driven and include structured mentorship and opportunities for feedback. Employers should incentivize staff and leadership to forge relationships with talent in WBL programs and refer their mentees for full- time employment opportunities. Some employers may establish their own WBL programs, while others may partner with postsecondary institutions, community- based organizations (CBOs), and social enterprises to coordinate these programs.

WBL provides Black talent with career and industry exposure, experiential learning, skill building, and access to new and varied relationships and resources. All too often, WBL programs don’t emphasize relationship building to help Black learners and workers access and utilize resources. By placing relationships at the heart of WBL, employers help their Black participants build professional social capital and make employment opportunities available to a diverse set of learners.

Capital One Coders pairs Capital One technologists with learners–78% of whom are students underrepresented in STEM–interested in pursuing computer science. Studies show the program is both boosting learners’ interest in STEM fields and driving significant gains in the participants’ professional social capital. INROADS, a career pathways program, offers its learners paid internships with more than 200 partner organizations; in addition to receiving customized skills training, they build relationships with corporate executives, peers, and INROADS alumni, and are paired with an advisor who offers both professional and personal coaching.

Partner for Intentional and Inclusive Hiring

Partner for Intentional and Inclusive Hiring

By building partnerships with institutions and organizations that have strong relationships with Black learners and workers, employers can build trust, raise awareness, and ultimately facilitate more equitable access to professional opportunities, resources, and relationships for Black learners and workers. Services may include promoting job opportunities, serving as resource navigators for new employees during onboarding, and developing training, career mapping, and mentorship programs. Employers should ensure that these partnerships are well-structured and well-resourced to maximize impact.

Shifts in workplace norms— driven by the pandemic, the resulting Great Resignation, and Gen Z habits and preferences—require employers to find new ways of engagement to recruit and retain a diverse workforce, including using social media to reach learners with smaller professional networks. Effective onboarding can improve employee retention, but only 12% of employees feel strongly that their employers succeed in this. By partnering with select CBOs and social enterprises with expertise in supporting Black workers, employers can more effectively address this challenge.

Boeing is leading the way in diversifying their workforce by partnering with HBCUs to recruit interns, many of whom are then hired full-time. Since 2019, Boeing has hired 266 HBCU interns, in addition to donating $2.4 million in 2021 to scholarships and programs supporting HBCUs. The OneTen coalition, which aims to place one million Black Americans in family- sustaining jobs by 2030, recently announced a partnership with Merit America to help train and hire Black workers without four-year degrees in remote-work opportunities. A majority of Black workers prefer remote or hybrid work: removing geographical constraints and partnering with a well-networked national nonprofit has helped many organizations build more diverse workforces. Other organizations are partnering with Mentor Spaces, a recruitment tool that scales mentoring conversations between underrepresented learners and workers and employers to diversify talent pipelines. The platform helps companies reach new and more diverse talent at scale, in addition to supporting existing employees.

Building: Leveraging Social and Professional Capital Throughout Employment

Employers can take essential steps to ensure Black workers translate social capital gains to advancement opportunities.

Provide Career, Relationship, and Resource Mapping

Provide Career, Relationship, and Resource Mapping

Managers should help workers create individualized plans to achieve their career goals with an eye toward connecting to organizational goals; this includes identifying the direct and indirect relationships each worker holds or could hold within the organization and how these may be helpful for their growth and advancement. Employers can design this process, or partner with CBOs or technology companies that offer internal mobility and advancement pathways solutions. Supervisors should also openly share information about advancement opportunities and pathways within the organization, ensuring that access to information is distributed equitably.

Research shows that strong social capital is critical to employee job satisfaction, performance, and retention. By offering both career and relationship mapping, employers can encourage employees to strengthen relationships while also offering information on growth pathways, both improving retention and employee satisfaction while also supporting productivity gains and internal mobility.

While relationship mapping for employees is still an emerging practice, career mapping has become a prominent strategy for leading employers. Prudential has invested in innovative mobility and reskilling efforts, including a Talent Marketplace that shows all staff career progression opportunities, timelines, and necessary skills, and a Skills Accelerator that helps staff upskill and reskill based on their goals and interests. Managers are encouraged to align team skills with future opportunities in the organization, and work directly with staff to help them learn new skills, stretch, and advance into new roles.

Formalize Mentorship and Networking Programs

Formalize Mentorship and Networking Programs

Employers should build ongoing and sustainable cross-organizational mentorship programs for both skill- and relationship-building. These should include formal one-to-one partnerships and opportunities to network across partnerships to expand social capital relationships. This can also include opt- in reverse mentoring–pairing interested junior workers with senior leaders to bring fresh perspectives and offer insight on strategic issues, leadership, and culture.

A study by Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations found that mentorship programs increase promotion and retention rates of underrepresented workers by 15%-38%, compared to non-mentored underrepresented workers. Mentorship that fosters feelings of inclusion and belonging is critical to retaining Black workers—a study by Bain & Company found that Black workers who feel excluded in the workplace are 2-4 times more likely to leave their jobs than white workers who are more likely to feel fully included. When paired with thoughtful preparation and training for senior leaders and robust support for early-career workers, reverse mentoring can empower junior workers, promote retention of underrepresented workers, and keep businesses abreast of technological and other cultural shifts.

In 2019, Caterpillar implemented the Guardian Program, a mentorship program focused on safety and network expansion; participating employees reported increased confidence and comfort in their roles. Caterpillar also offers workers who are recent college graduates access to a professional development program—a three-year rotation focused on networking, training, and mentoring opportunities that vary depending on career area.

Expand Sponsorship for Black Worker Advancement

Expand Sponsorship for Black Worker Advancement

Sponsors actively advocate for their beneficiaries in the workplace: ensuring leadership is aware of their contributions, suggesting them for priority projects, and backing them for advancement opportunities. Staff should be trained on how to create inclusive cultures, and how to provide mentorship and sponsorship relationships in culturally relevant and equitable manners. Organizational leaders should actively work to ensure their support goes to all high-performing staff, regardless of personal relationship or demographic characteristics. Human resources and executive leadership should support accountability.

A recent Harvard Business Review report noted that while 20% of white employees report having sponsors, only 5% of Black employees do. However, when Black employees are sponsored, they are 60% less likely to quit within a year than peers who are not sponsored, and Black managers are 65% more likely to progress to the next rung in the ladder if they have a sponsor.

Ernst & Young offers formal, equitable sponsorship to increase racial, ethnic, and gender diversity across their leadership and drive the advancement and promotion of their workers. Representation of Black leaders on their U.S. Executive Committee increased from 6% to 13% in one year. Black workers also saw a 5% increase in promotion to principal or partner.

Expanding: Investing in Workers’ Lifelong Careers

Employers can invest in Black workers’ social capital to help build lifelong careers, and take proactive steps in reducing the racial wealth gap.

Educate and Advocate for “Brand- Building”

Educate and Advocate for “Brand- Building”

Leadership should model and encourage the creation of a professional brand to help workers expand their professional social capital, networks, and long-term advancement and earning potential. Employers can support Black workers in particular by encouraging or subsidizing enrollment in organizations like Calibr –a Black professional network–outside of the workplace. More broadly, employers can invest in professional development opportunities that help workers use networking platforms and social media to grow their professional connections, and encourage them to take on external speaking and publication opportunities.

As discussed throughout this framework, social capital and “who you know” play a significant role in workers accessing advancement opportunities, and personal brand-building is a way to build the professional relationships and reputation that lead to advancement. Empowering workers to build strong personal brands, including through thought leadership, can help them gain prominence in their field and for individual organizations, even after they advance.

Many financial institutions, like Citi, have early identification programs for Black students. During these work-based learning opportunities, these organizations support Black learners to better understand how to build a professional brand and understand their current assets. These kinds of practices can and should be applied to full-time employees as well. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP has developed workbooks and other resources to support employees in exploring their personal brand. This is still an emerging practice and we hope to see more employers adapting these resources and utilizing them with staff.

Bring Alumni Engagement to the Workplace

Bring Alumni Engagement to the Workplace

Engaging Black workers who have moved on to other organizations offers an opportunity to invest in the social capital of both current and former employees. Staying in touch via newsletters, sharing job openings, and inviting them to casual meetings and networking sessions with current staff offer opportunities for mentorship and relationship-building. Employers may consider creating a database for current employees to access to continue to build upon and expand their networks.

Alumni programs help improve brand recognition, business development, and talent acquisition, and can serve as a source of targeted recruiting for underrepresented populations. Alumni who engage in an alumni program are also 32% more likely to recommend the company’s products and/or services.

Organizations like Deloitte and Sodexo use alumni networks to recruit former employees. 20% of Sodexo’s annual hires, for example, are former employees. Management consultant organizations like McKinsey & Company boast particularly strong alumni networks, partially by enrolling all current employees into the network as soon as they join the organization, rather than when they leave, and by maintaining strong online databases, social media, and newsletters so alumni can stay in touch.

Metrics & Evaluation

Across these strategies, it is critical that employers evaluate and benchmark progress within these initiatives, including identifying and monitoring key performance indicators.

These may include:

- Application, hire, retention, and advancement rates for Black workers

- Employee satisfaction overall and with their managers

- Alumni engagement rates

- Growth in workplace, LinkedIn usage and network sizes, and more

For more resources and guidance, please see University of Pennsylvania’s ImpactED and the Christensen Institute’s framework for measuring relationships and networks. As noted earlier in the framework, the effects of social capital creation, particularly among Black workers, remain understudied, and evaluation efforts are critical to strengthening our success and impact.

Conclusion & Areas for Future Work

While a truly egalitarian society would not rely on social capital, in today’s world building professional social capital is a critical element of promoting economic advancement. While many stakeholders across education, policy, research, and more have a role to play in this work, we believe employers and postsecondary education and training providers can take a significant leadership role in adopting strategies that can make it far easier for Black learners and workers to gain and use professional social capital.

|

To apply this framework as envisioned, postsecondary and employer stakeholders should begin by establishing four key conditions needed to effectively support Black learners and workers in their pursuit of social capital.

|

While this framework emphasizes the actions each of these two stakeholders should lead, we are also aware of the many ways in which they must collaborate to help Black learners and workers build and maintain social capital as they move in and out of education and work throughout their lives. We also note that there are many other stakeholders who can and do promote social capital creation, from K-12 schools, community-based organizations, policymakers, social entrepreneurs, technologists, and more. Areas for future research and work include pursuing further efforts to quantify, understand, and measure the impact of social capital on education and economic outcomes, connecting this research to further areas of inquiry around key wraparound and holistic support for Black learners and workers, and identifying key actions stakeholders not accounted for in this framework can take to expand professional social capital for Black learners, including developing systemic policy recommendations.

We look forward to further partnership efforts to ensure all Black learners and workers are able to build professional social capital to support their economic advancement, disrupt occupational segregation, and ultimately close the Black-white wealth gap.

Additional Resources

Accelerating Black Economic Advancement

Achieving Black Economic Equity