Introduction

Data are essential to prove the efficacy of an intervention, to demonstrate the need for a new approach, or to simply understand how our individual efforts add up to systems-level trends. In their work designing and advocating for more equitable pathways systems that span education to careers, intermediary organizations use data from multiple sources. Internally, they monitor and evaluate program performance. They also rely on data from across education and workforce systems to reveal trends and identify areas for greatest impact. Identifying cross-systems trends requires responsibly painting a picture by looking across K–12, postsecondary, and labor market data.

Working with diverse data sets, intermediaries ask—and work to answer—questions such as:

- Who advances and who gets left behind at key transition points between secondary, postsecondary, and workforce systems in our program?

- What is the significance that X percent of Black students in our program graduate with a STEM associate’s degree? Are we doing well or poorly from an equity perspective?

- How do we compare local or programmatic data with state and national trends?

- How do we track postsecondary pathways into the regional labor market when data sets follow different timelines and individuals?

This brief seeks to identify the necessary conditions within an intermediary and its ecosystem for enabling responsible data collection and analysis, empowering data-driven decision-making, and pursuing systemic and equitable change.

|

Data Enablers

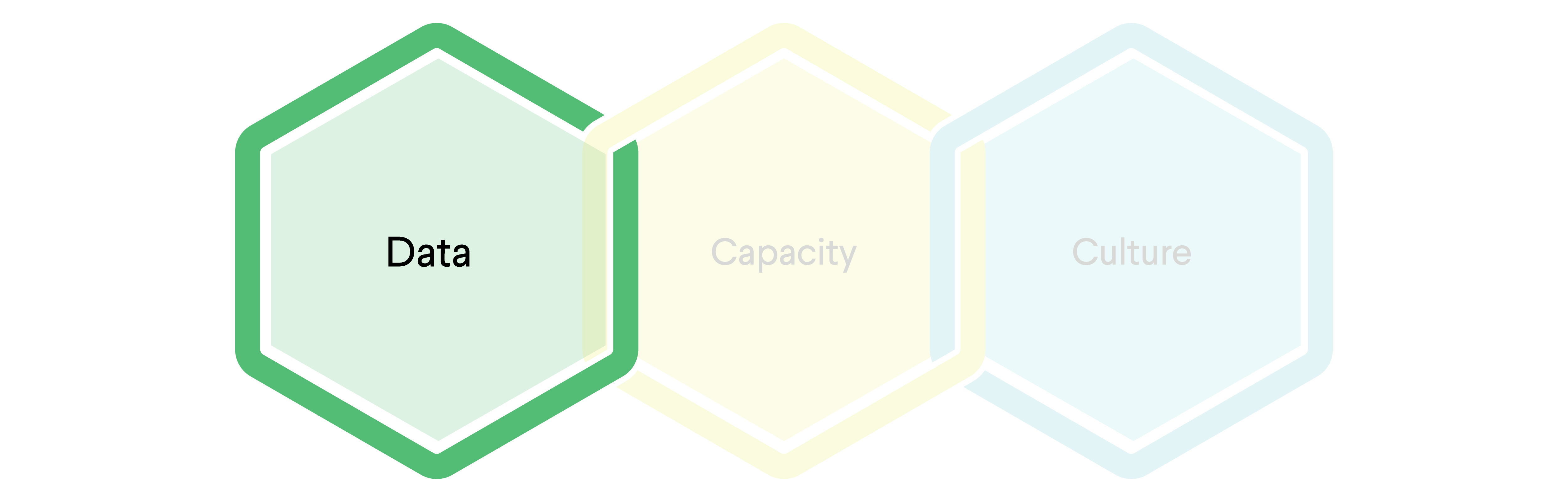

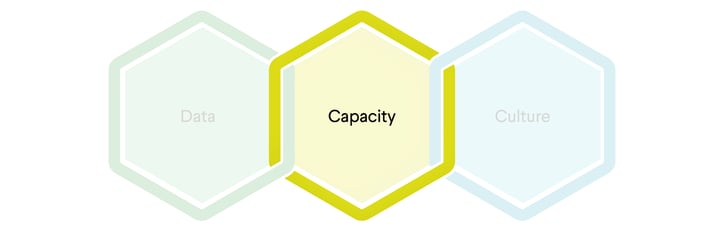

What is a data enabler? In brief, it is a person, thing, or condition that makes something possible. The term enabler is adopted from the policy world’s practice of identifying the necessary conditions to enable a new policy to take root. Enabling conditions for cross-system equity analysis include 1) access to priority data sources and types, 2) adequate data capacity of the intermediary’s staff, and 3) a culture appreciative of the evidence data provides.

Each enabler allows for a different level of analysis and action, working together to inform what the data does—or doesn’t—make possible. For example:

- Collecting more data won’t necessarily help us close equity gaps if it isn’t disaggregated (see here).

- Having disaggregated data won’t necessarily help us close equity gaps if the staff capacity doesn’t exist to communicate findings with people empowered to act on those findings (see here).

- Communicating findings to people with the authority to act won’t necessarily help us close equity gaps if definitions of success and accountability aren’t shared (see here).

Individually, these enablers may seem obvious, but together they create a road map toward a robust data ecosystem that centers equity. Each enabling condition is key to designing, building, and evaluating effective pathways work in terms of how it aids or inhibits the use of data for positive impact. Each requires partnership and collaboration, investments in technical tools and capacity, and strategic mapping of available data to address collective priorities. Intermediaries play an important role in advancing these enabling data conditions. But the end goal in using this data is to help youth, educators, employers, funders, and policymakers feel equipped and empowered to make changes—both individual and systemic—that lead to more equitable pathways.

1. Data

Intermediaries access, analyze, and share data—both program data and public data (see Appendix A)—to enhance their work with regional partners to guide equity analyses and inform pathways strategies. Program data are collected internally on a given program (e.g., a career and technical education (CTE) program or an apprenticeship program); public data are available from myriad sources, such as the U.S. Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and state labor market information (LMI) agencies. Public data can supplement and contextualize the data intermediaries collect about their own work or that of partners. Intermediaries help determine what existing data, or new data, can best inform steps toward more actionable processes and outcomes. For more on specific pathways data sources and types and the differences between program and public data, see Appendix A.

|

-

1.1

Condition:

Data disaggregated by demographics

What it Enables:

In seeking a world where the identities of historically oppressed groups no longer predict individuals' economic outcomes, disaggregated data can pinpoint where such trends persist and where tailored or broad interventions are necessary.

Examples from the Field

CareerWise Colorado relies on detailed programmatic and demographic data on apprenticeship program participation to observe trends in real time. They found that attrition was higher for Black and Latinx youth in the first 90 days of programming. Recognizing this pattern allowed CareerWise to make programmatic changes early in the apprenticeship year, working with high school and employer partners as part of their Equity First initiative to close these gaps.

HERE to HERE looked at microdata (e.g., person-level data) from the U.S. Census Bureau and found that even among those with a bachelor’s degree, Black and Hispanic workers in New York City were twice as likely to work in low-wage occupations than in mid- to high-wage occupations. The organization published their findings in the report, The Key for an Inclusive Economy, which helped make the case that the city needed to rethink their educational and talent development systems to reduce these disparities.

YouthForce NOLA developed an ecosystem evaluation model that uses student readiness and system change indicators. They mapped these indicators, most of which came from a compilation of data from the Louisiana Department of Education Student Transcript Systems, reports from individual secondary schools, financial reports, their own programmatic database, and surveys. Across the ecosystem indicators, data can be disaggregated by equity and demographic subgroups. This pairing of data and deep analysis gives the organization fuller insights into the present state within their region as well as a more nuanced vision for where they want to go.

-

1.2

Condition:

Process data as well as outcomes data

What it Enables:

Outcome data related to student education completion or employment tells us what happened as the result of an intervention but not where the patterns and trends observed were established. For the latter purpose, intermediaries need information on the process or steps along the way to an outcome (e.g., activities and participation trends) to pinpoint when and where trends are established and where changes are needed.

Examples from the Field

Instead of waiting to review outcomes at the end of the academic program, Connecticut State Colleges and Universities (CSCU) developed a set of key performance indicators to see how students are doing as they progress in their studies. The 23 indicators are available as trends and can be disaggregated by gender, race/ethnicity, age group, and zip code. System leadership uses the indicators to understand the effect of interventions as they are rolled out across the community colleges in the system.

EmployIndy mapped career navigation data onto resulting actions taken by stakeholders in Central Indiana. To better inform the reality of these resulting actions, EmployIndy worked with stakeholders—including students, caregivers, middle and high school counselors, and community program staff—to identify junctures where data could inform interventions. In one example, the team identified that a school counselor might see the data point of a student’s GPA and use that to recommend placement in a dual credit or AP class.

-

1.3

Condition:

Qualitative AND quantitative data

What it Enables:

High-quality qualitative analysis provides powerful insights into how to effectively deliver pathways programming and adds valuable context to quantitative data. Qualitative data can also be an important tool for centering youth voices in decision-making processes.

Examples from the Field

Washington STEM partnered with Eisenhower High School in Yakima, Washington, to collect quantitative and qualitative data that challenged assumptions about students’ pathways aspirations and preferences. Staff thought roughly 56% of their students expected to attend postsecondary schooling; it was 89%. Staff were also surprised to learn that their Gen Z students were averse to getting career guidance from social media; they preferred in-person guidance from teachers. Because of the documentation and findings from the project, Career Connect Washington is changing their approach to supporting K–12 career navigation. (See The High School to Postsecondary Toolkit.)

HERE to HERE used quantitative state employment data to show the growth opportunities for creative occupations in New York City, simultaneously demonstrating how Black and Hispanic workers are underrepresented in the field. In their report, the organization paired that data with interviews with young people, using that qualitative data to speak to a wide range of factors that keep many young people of color from pursuing their creative interests as careers in a way the quantitative data alone would not have done.

|

2. Capacity

To conduct the analyses described above, intermediaries need partners or their own staff to build the skills to collect, access, analyze, understand, and communicate information. Like any organization, intermediaries are limited in their capacity, namely by the extent of their access to the resources, tools, and staff capacity and skills necessary for this high-impact work. Data capacity encompasses the ability of intermediaries and partners to collect, analyze, and use data and the amount of time they have available for this work. The quality of the resources, tools, and abilities all contribute to the ultimate impact in the field. Intermediaries shouldn’t be responsible for doing all the pathways data work in their region, but they can be instrumental in coordinating the enabling conditions that ensure the data work happens.

|

-

2.1

Condition:

Access to the data you need when you need it

What it Enables:

Data-sharing agreements can facilitate pairing data sources to show a more complete picture of student trajectories and outcomes, including potential disparities and areas of intervention. These agreements can underpin data systems that provide real-time access to data for key stakeholders and partners.

Examples from the Field

Education Systems Center (EdSystems) leverages the Illinois Longitudinal Data System, which connects secondary, postsecondary, and state workforce system data alongside federal data to inform educators on dual credit trends and remediation rates. But EdSystems had to establish separate direct data-sharing agreements with school districts and community colleges to disaggregate much of that data from the longitudinal data system. These relationships were critical in providing more nuanced data to explore barriers and successes across student groups.

-

2.2

Condition:

Ability to synthesize and interpret data

What it Enables:

Many organizations reach a decision point about the extent to which data analysis will be managed in house, actively distributed among partners, or simply be left up to a general audience. This choice guides decisions around staff members’ time and skills in determining the strengths and limitations of the data and what the data represent.

Examples from the Field

To synthesize labor market trends more quickly, many intermediaries use subscription-based services such as Lightcast or data platforms like JobsEQ or Public Insight. Intermediaries that pay for these services still need staff or partners with the skills and time necessary to use them.

The WE CAN TX program at Educate Texas heard from community colleges and workforce boards that they could access data related to work-based learning through public data sources and paid reports, but they still didn’t have a reliable one-stop shop for data to inform industry-aligned curriculum and understand talent trends for high-demand sectors and jobs. In response, WE CAN TX developed an education-to-workforce dashboard with visualizations that prioritize data that can drive decisions among partners. They focused on usability and simplicity, emphasized equity by providing disaggregated data, and included “sliceability” by geography (see related case study).

-

2.3

Condition:

Ability to communicate with different audiences

What it Enables:

By understanding partners’ interests and goals, intermediaries can identify what questions they hope to answer through data and the relevant data needed to answer them and serve as accountability partners in making progress toward equitable outcomes.

Examples from the Field

When launching a new apprenticeship program, Say Yes Buffalo used data to guide program design. They made the case with employers to avoid additional student testing during the application process. They used qualitative data from youth to create a welcoming interview process where employers met with students at school in casual attire. The organization also created data processes to iteratively adapt a mentorship program. In each case, they adapted how the data was presented in reports and dashboards and as conversation talking points to best communicate to the various stakeholders how to help make an apprenticeship program a success.

-

2.4

Condition:

Dedicated capacity for feedback loops

What it Enables:

Making feedback loops predictable and routine, with connections back to goals and priorities, ensures partners stay aligned on their joint goals. Intermediaries can center community-informed and equity-focused pathways by dedicating staff to gather stakeholder feedback on the data they find most useful as well as the most effective ways to visualize and share that data.

Examples from the Field

Career Connect Washington and Washington STEM established several externally facing tools including a labor market credentials dashboard, a credential opportunities dashboard with data by region and industry, and a student-facing directory. But they still carve out staff time to work closely with their nine local networks—which deeply understand the K–12 school districts, community colleges, and employers in their regions—to learn how the dashboards can best complement other tools those stakeholders are using. This ensures the dashboards are living tools that evolve to help stakeholders answer questions they have within their regional context.

Urban Alliance’s Research and Evaluation Department creates an annual internal report that breaks down evaluation results for all programs. In the interim, the department provides program staff with updates (presentations and data repositories) as analyses occur. Additionally, the department strives to democratize data by sharing feedback results with program participants, mentors, and program staff. They are currently partnering with their Youth Advisory Council to determine additional ways to share information with program participants, the larger organization, and external partners.

|

3. Culture

Data culture encompasses both the culture of the intermediary organization internally as well as the culture across the organizations the intermediary interacts with in the pathways ecosystem. Intermediaries constantly navigate this ecosystem, forging relationships, championing policies, and implementing and analyzing practices that ultimately support equitable pathways. This culture can be explicit, codified through data-sharing agreements, or implicit, showing up in the learning mindsets of intermediaries and partners.

|

-

3.1

Condition:

A shared vision and action plan

What it Enables:

Outlining how the secondary, postsecondary, and workforce development systems fit together, and what the end goal of their combined work should be, is essential in pathways work. A shared vision and action plans create stronger, more trusting partnerships and can lead to greater impact on learners and influence in the field.

Examples from the Field

The Baltimore Data Youth Hub established a series of foundational principles for their collective data work, namely:

- understanding historical context

- prioritizing transparency and trust

- strengthening systems and coordinating services

- eliminating racial disparities and inequities

- ensuring data privacy.

When state agencies publish their research agendas, they foster transparency and signal opportunities for partnership. KYStats works with school districts and workforce boards in Kentucky, relying on them to guide and help execute a publicly posted research agenda that will be useful to policymakers and practitioners.

CityWorks DC worked with the D.C. Policy Center to produce an in-depth report and event promoting the importance of tracking early-career outcomes of the city’s youth so stakeholders can regularly access findings and create strategies to rectify barriers. Meanwhile, a parallel survey they conducted showed that many learners and earners with a bachelor’s degree were in jobs that did not require one, raising concerns about their long-term career trajectory. Combined, these efforts created the necessary momentum with city leadership to prioritize establishing a P20W (education-to-work) data system, providing access to linked educational and employment outcomes data.

-

3.2

Condition:

Consensus on definitions

What it Enables:

Even across disparate systems, shared definitions and language reinforce—and at times can define—shared goals and allow for greater transparency and accountability.

Examples from the Field

The WE CAN TX initiative at Educate Texas narrowed down a list of more than 80 potential process and outcome indicators to prioritize eight of the most meaningful, measurable, and movable pathways indicators. Success indicators include both student and regional-partner-based metrics. While additional process and outcome data will still be collected, the short list of common success indicators across regional partners will ensure efforts remain aligned and participants can hold one another accountable to shared definitions of collective aspirations.

-

3.3

Condition:

Privacy and security mindset

What it Enables:

Protecting the privacy and security of data underscores a learner-centered approach. Partners need to communicate openly and transparently about:

• privacy standards (e.g., encryption, storage standards, when to de-identify data, etc.)

• privacy and security risks

• who has access to what data, for how long, and for what purposes.Examples from the Field

The University of Pittsburgh communicates openly with students about which of their data points are shared with whom.

CSCU’s data-sharing work is guided by the Fair Information Practice Principles, national data security standards, FERPA, and other relevant laws (such as the Higher Education Act) to ensure student privacy is protected and data security maintained. They are also working with the state P20 WIN (the state's longitudinal data system) system to develop a security process that includes a security questionnaire data seekers must complete so data providers can understand the security risks of the data-sharing project.

-

3.4

Condition:

Strong learning culture

What it Enables:

Critically examining data in a community that embraces vulnerability, trust, and willingness to learn facilitates systems that are more impactful and innovative. If partners are willing to see what works and what doesn’t, students ultimately will benefit from responsive systems.

Examples from the Field

EdSystems works with communities to conduct their own data integration. Creating spaces for reflection is key, so that district and college leadership can look at the data from public and internal sources, find insights, and create action. EdSystems then works to see that the information is brought to educators in more student-facing roles, such as principals and faculty. The trusting relationship between EdSystems and local partners is critical—not only to enable access to data but also to create those vulnerable spaces for learning and reflection so that needed changes can be made.

-

3.5

Condition:

Accountability

What it Enables:

A collaborative culture and codified agreements between state and local agencies and legislatures can be powerful tools in establishing and maintaining norms of behavior, policies, and procedures that result in regular cross-agency reporting, collaboration, and action.

Examples from the Field

In Colorado, 24-46.3-103 C.R.S. requires the Colorado Workforce Development Council to publish an annual Colorado Talent Pipeline Report in partnership with the Department of Higher Education, the Department of Education, the Department of Labor and Employment, and the Office of Economic Development and International Trade, with support from the Office of State Planning and Budgeting, the State Demography Office at the Department of Local Affairs, and other partners. Presented to the legislature and shared externally, the report is a mechanism for all agencies involved to assess the current labor force regularly and collaboratively, opportunities for growth, and talent development strategies.

|

Data for Whom:

Key Customers for Equity Data

The enablers connected to data, data capacity, and data culture are foundational conditions that support equitable pathways design but are essential only in that they enable stakeholders across the education and workforce ecosystems to collaborate for change. Each stakeholder group understands data to varying extents and uses it for distinct purposes. Intermediary organizations use data to equip and empower these key stakeholders, detailed below, to build more equitable pathways through program design, advocacy, and individual decision-making. For examples of metrics used by the stakeholders below, see Appendix B.

At best, intermediaries work to increase opportunities for youth to advance their data literacy on issues close to their experience and to lend their expertise and perspectives to data interpretation. Intermediaries may provide data to youth directly as well as to schools and community-based organizations that provide youth with data on training, jobs, and wages. Intermediaries also help young people become aware of the extent to which data are collected about their activities and that adults draw conclusions from this data, which may affect their education and training in both positive and negative ways.

Intermediaries work with secondary- and postsecondary-level educators who are in student-facing roles (e.g., instructors and college and career counselors) or leading schools or systems (e.g., superintendents, principals, or deans) to provide timely data about their students. After students leave high school, school officials need help tracking student pathways to evaluate the success of their school in launching careers.

Employers, industry councils, and business associations are often unaware of what information they have and whether it could be useful in efforts to improve education and workforce systems. They are also hesitant to share their data, often preferring that it be anonymous or reported in the aggregate. Intermediaries can design responsible and effective uses of employer-provided data and complementary LMI to identify skills and competencies that are needed now and in the future. Intermediaries also supply employers with data on educational programs that feed into their in-demand jobs and analyses of hiring and retention practices aligned to employers’ equity goals.

Intermediaries use data to meet funders’ requirements for evidence that a program is meeting its benchmarks and outcome goals. Public and private funders want to know which projects in their portfolios have the greatest impact, including which might rise to the level of an evidence-based best practice for others to emulate in their own context. Intermediaries may also help pair programmatic data with regional data to help guide and support funders’ efforts within certain geographic areas. Much of the data work between intermediaries and funders takes place in the form of formal evaluations—ranging from implementation studies to randomized controlled trials—and regular reports.

State and local agencies, including workforce development boards, community college boards, and departments of education and labor, often have access to large quantities of data. Even so, they often do not have the resources, staff, agreements, or technical capacities needed to consistently produce reliable metrics to guide policymaking related to pathways improvements across K–12, higher education, and employment systems. Intermediaries can establish formal and informal partnerships with policymakers to help them make sense of the data they have, contributing to more strategic use of resources, actionable information for partners and contractors, and legislative advocacy on behalf of other stakeholders.

Understanding various stakeholder groups, and how they understand and use data, is an essential piece in mapping out your own data ecosystem.

|

Surveying Your Ecosystem

The above enabling conditions are illustrative of the experience of members of the Building Equitable Pathways community of practice and are not meant to be exhaustive. Each intermediary has their own data system needs and unique challenges.

Use this tool to think through the way your organization currently uses data, in both an evaluative sense and to empower others.

Conclusion

|

|

Where the Field is at

Currently, each locality and each organization is left to patch together the data they can readily access to conduct an equity assessment of pathways in a region. One organization might rely solely on federal census data while another might rely on their own programmatic data alongside data they gather from individual employers.

Because we typically don’t have a unified consensus on what, if any, pathways data should be available, how often, and to whom, we have perpetuated a system that relies on the strength of individual trusted relationships or the know-how to navigate complex data-sharing agreements. The ability to then interpret that data in effective and timely ways hinges on funding—for staff, for access to paid services that shorten the time it takes to pull data together, and for platforms and mechanisms for communicating data findings in timely and actionable ways.

In part because we use different data sets—most of which are too different to be analyzed side by side—and our systems are siloed in various ways, we don’t have a unified picture of what is actually happening. A school superintendent’s understanding of equitable pathways can be very different from that of a college dean, which again, might differ drastically from that of the local chamber of commerce or an elected official. Even state longitudinal data systems differ in who has access to the data or related reports to inform what analysis should even take place. This in turn affects our ability to unite around shared definitions of equity solutions that address the root causes of inequality.

In short, we have some general sense of agreement in the field about the importance of individual metrics for measuring equity in pathways (see examples in Appendices A and B), but the data we use to inform those metrics—and who has access to what data and when—vary widely within and across geographies. Even within the Building Equitable Pathways community of practice, no two organizations have the same experience with, or access to, the enablers outlined in this brief.

Where We Want to Be

Increasing the number and scope of regional partners experiencing most of the enabling conditions described here is something we can address through intentionality and by way of funding and policy decisions at the local, state, and federal level. For example, the states of Washington and Connecticut have made great strides in the ways in which they gather, process, and share wage record data. In Connecticut, employers are now required to report detailed information including employees’ gender identity, age, race, ethnicity, veteran status, disability status, and highest education completed—a huge step in enabling an equity analysis to even take place.

Looking to the future, intermediaries are well positioned to provide a clear-eyed assessment of where their state or region is currently at in each of these enabler categories. The goal is to bring stakeholders together around a united data vision and plan, sparking changes to how we determine what data are important, how we prioritize data staffing and skills, and how we can collaborate differently and hold one another accountable in service of more equitable pathways.

Appendices

-

Appendix A

Intermediaries leverage data from multiple sources. Each data source is a potential tool to interrogate and use to shape narratives that change the way key partners support youth and, by so doing, strengthen their regional and state economies.

Data Sources and Types

Program Data

Intermediaries vary in the degree to which they work with youth directly. For those that do work directly with youth, they collect important, they collect important pathways programmatic data, including:

- quantitative data, particularly around youth demographics, work-based learning engagement, and alumni outcomes, as well as employer work-based learning engagement and outcomes

- qualitative data regarding employer feedback and youth programmatic learning, soft skills development, and experience satisfaction.

Program data may include: the number of interviews students go through versus the number of offers made; internship completion rates; and the percent of work-based learning programs that end with full-time job offers.For examples of education-to-workforce indicators, including individual-level outcomes and milestones alongside adjacent systems conditions, read Mathematica’s report Education-to-Workforce Indicator Framework: Using Data to Promote Equity and Economic Security for All.

Public Data

Nearly all intermediaries use public data to analyze larger education and workforce trends in their region.

- Much public data is collected by local, state, and federal agencies from individuals and employers via voluntary and mandatory mechanisms. Intermediaries may have close relationships or data-sharing agreements with individual state agencies, including state secondary or postsecondary education and workforce agencies.

- Public data may include data posted on the internet or qualitative and quantitative data compiled and shared by local economic development agencies, chambers, industry groups, workforce development boards, or sector partnerships.

- State longitudinal data systems—accessed directly or through an education district’s student information system—can enable cross-system analyses that identify trends in how individuals navigate education and career. In many states, however, K–12 and college data are not connected, and career outcomes are often left out of the longitudinal data system (LDS). Even when this information is included and connected, it can be difficult for actors outside the state agencies to access it. It may even be difficult for state agencies to access data they don’t produce themselves. Each state’s LDS comprises different data. To see the status for your state, see individual state profiles from the Education Commission of the States.

Public data may include: credential attainment rates, wages post-graduation by degree, historical employment, and forecasted job openings data by sector and occupation.To learn more about specific data sources, particularly at the federal level, see the Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness’ A Brief Introduction to Labor Market Information. For more information on the application of LMI to pathways, see From Labor Market Information to Pathways Designs: Foundational Information for Intermediaries.

-

Appendix B

Grounding equitable pathways design in actual data points used by stakeholders across the ecosystem—youth, educators and institutional leaders, employers, funders, and policymakers—can be helpful to understand where and how this work happens. The following are sample data points intermediaries may use for and with different stakeholders:

General

- Demographic data for the region

- School and program alumni feedback data

- Soft skills or essential skills acquisition data

- Student/worker experience data

Education (Inclusive of Secondary and Postsecondary Education)- Data on remedial coursework trends

- Enrollment data for pathways degrees and coursework

- Data on availability of pathways coursework at the secondary and postsecondary level

- Demographic data to discern under- or overrepresentation by pathways program

- Graduation data for pathways degrees and coursework

- Employment rates and wages for pathways programs

Transitions between Education and Work- Local work-based learning data (including availability of different types of work-based learning and participant and outcome data)

- Credentialing course enrollment and attainment data (from schools and training providers)

- Availability of career navigation services and related data collected at each stage

Employment- Employment rates and forecasted demand for labor by sector and occupation

- Wages and job quality information and trends by sector and occupation as well as by demographic

- Demographic data to discern under- or overrepresentation by sector and occupation

- Job postings and data on experience or degree requirements

JFF Publications

High-Quality Work-Based Learning: State Policy Recommendations to Build Clearer Paths to Postsecondary Success

Partner Publications

Unlocking Potential: A State Policy Roadmap for Equity and Quality in College in High School Programs

Partner Publications

Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship: Principles for High-Quality Apprenticeship

JFF Publications

Better Connecting Secondary to Postsecondary Education: Lessons and Policy Recommendations from the Great Lakes

JFF Publications

The Big Blur: An Argument for Erasing the Boundaries Between High School, College, and Careers—and Creating One New System That Works for Everyone

JFF Publications

No Dead Ends: How Career and Technical Education Can Provide Today’s Youth With Pathways to College and Career Success